Trans-Canada Highway History and Construction

Watch for the grey buttons around the site, which denote TCH History details, compared to the usual blue buttons which provide community information around the site.

Watch for the grey buttons around the site, which denote TCH History details, compared to the usual blue buttons which provide community information around the site.

The Trans-Canada Highway history chapters are organized (roughly) in chapters that match the itineraries, and specific communities. You can access the History Chapters from other content (and go back and forth), or you can navigate sequentially through the all of the Itinerary Segments, or through all of the History Chapters.

When on the Itinerary pages, just look for the GRAY BUTTONS!

![]() Provincial TCH History

Provincial TCH History

![]() Itinerary Segment History

Itinerary Segment History

For reference, you can read these in conjunction with our Large scale route map

Construction of the Trans-Canada Highway began in 1950 with Parilament passing the Trans-Canada Highway Act. This authorized the Government of Canada and provincial governments to build the highway on a cost-shared basis. The Trans-Canada Highway is Canada’s longest national road connecting across Canada from Victoria, British Columbia to St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador (with car ferries linking both Newfoundland and Vancouver Island to the mainland). The Trans-Canada Highway passes through all ten Canadian provinces and linking Canada’s major cities.

The main route was opened up in 1962 by Prime Minister John Diefenbaker, but parts were not completed until 1971. In 1970, a northern route called Yellowhead Highway (Highway 16) was officially opened across Western Canada.

But the highway did not begin with this Act of Parliament, but rather was an evolution through various means of transport use to get people across this vast continent, even before Canada declared itself a country in 1867.

Canada is an interesting country. Considering its vast size, as the second largest nation in the world (after Russia – still), it amazes people from other parts of the world how we are so similar in language and in our daily lives. There are few pronounced regional dialects (the Newfoundlandic English is the most unique) because—despite its size-this country EXISTS because of efficient transportation. Few areas feel isolated, despite their distance from other parts of the country. We all feel like part of a single country (Quebec may occasionally feel like the exception)

Explorers and settlers arrived in Canada as early as 1500 after sailing only a few weeks from Europe. Fur traders could reach far inland and back by canoe from either the French settlement of Hochelaga (now Montreal) or from the English “factories” along the Hudson’s Bay. But such fur-trading and exporation trips typically took a summer season to head out, and took the next season to head back,

Before the railroad, crossing Canada took three months by oxcart, horse and boat, as Sir Sanford Fleming did in 1872 travelling from Toronto to Victoria to determine the course for the proposed trans-continental railway to link to the new province of British Columbia. The railway brought coast to coast travel time to about a week, after 1885.

In the late 1800s, steamships brought European immigrants to Canada in only two weeks, and railroads quickly delivered them to the prairies to homestead in Canada’s “Last Best West”. The diverse linguistic and cultural mish-mash melting pot of Canada’settlers intermingled into a surprising homogenous culture and language. Much credit should go to the public school system which taught immigrants English so they could talk with their neighbours (usually from another country) in a ‘neutral’ third language.

In the late 1800s, steamships brought European immigrants to Canada in only two weeks, and railroads quickly delivered them to the prairies to homestead in Canada’s “Last Best West”. The diverse linguistic and cultural mish-mash melting pot of Canada’settlers intermingled into a surprising homogenous culture and language. Much credit should go to the public school system which taught immigrants English so they could talk with their neighbours (usually from another country) in a ‘neutral’ third language.

In the 1900s, the biggest force in Canada’s growth was the rise of telecommunications. The telegraph came with the railway, and moved information coast to coast in minutes. Towns and cities soon got newspapers, which created a shared experience in news, opinions, products and fashions.

At the turn of the century the telephone began to dominate interpersonal communication, even over long distances. By the 1920s radio gave a common identity through music, professional sports, and news, leading to the rapid rise of jazz music, big band and later rock ‘n’ roll. The moving pictures and later the “talkies” meant that Canadians also absorbed the influence of American culture.

About that time, the automobile moved into common usage. First mass-produced by Henry Ford in 1903, it enabled the Americans had cross their country from San Francisco to New York in 1906. Canadians had to wait until 1912 when Thomas Wilby crossed from Halifax to Victoria in 2 months, though he covered much of northern Ontario by railcar or on the deck of a steam ship, since there where still no cleared roads through that region at that time.

Between the two World Wars, airplanes began to speed transportation in the country and across it. They could fly across the Great Lakes and over mountain ranges in a straight line faster than any land-based transportation. Planes had their biggest impact in Canada’s North where settlements previously several day’s canoe trip or dogsled run from the nearest town were now an hour away by plane. Float planes landing on Canada’s myriad lakes and rivers connected small or isolated communities that could not justify expensive roads and railways.

World War II and its aftermath put Canadian growth into overdrive. Canada’s specific contribution to the British Commonwealth’s war effort was the establishment of airports coast to coast along with pilot and flight crew training schools across Canada, which were used to safely train pilots from Canada, England, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, and more. The Alaska Highway was built in months to connect isolated Alaska with Edmonton, Alberta to help defend America’s northern outpost against a threat of Japanese invasion. And a northern highway was built connecting North Bay and Nipigon and all the war-mission-critical mining towns scattered across Northern Ontario (critical for iron, cobalt, nickel, aluminum, and uranium, for planes, trucks, tanks, and bombs) which became todays Highway 11 Northern Route.

After the war, Canada was bursting at the seams from the millions of new immigrants from all corners of the globe. In the 1950s, the railway was still king in Canada’s transportation system, but the country was working to build and paved roads between the major cities fueled by the post-war growth of automobiles in Canada’s cities. By 1949 the Trans-Canada Highway act was passed by Parliament right after.

In the 1950s the American government began its massive interstate highway construction program with 4 lane twinned roads in all states (even Hawaii has “interstate” highways!). The jet plane meant it was possible to cross the country in a day, and hop across the Atlantic overnight, and made flying affordable for the middle classes. Television added a new way to communicate over distance, but also created a dramatic way to share experiences, news and emotions. The advent of satellites in the 1960s made it possible to instantly bounce TV signals around the world. It was Canadian media guru Marshall McLuhan who coined the phrase “the medium is the message”.

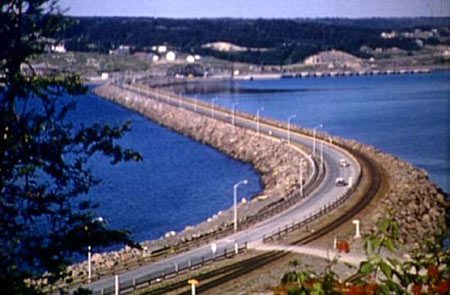

Newfoundland’s decision to join Canada also changed the process. It became important to connect all the provinces together by highway, and build the Canso Causeway to join Cape Breton to the Nova Scotia mainland and speed travel and shipping time to Canada’s newest island province.

By 1956, the federal and provincial government came to a cost-sharing agreement to encourage the provinces to upgrade existing roadways to “Trans-Canada” standards, and receive 90% of the cost of building new stretches to fill gaps in the roadway. This was most notable in mountainous British Columbia, the rugged Canadian Shield north of Lake Superior, and across much of Newfoundland. The goal was to connect all 10 provinces by paved road by 1967, Canada’s centennial year.

By 1956, the federal and provincial government came to a cost-sharing agreement to encourage the provinces to upgrade existing roadways to “Trans-Canada” standards, and receive 90% of the cost of building new stretches to fill gaps in the roadway. This was most notable in mountainous British Columbia, the rugged Canadian Shield north of Lake Superior, and across much of Newfoundland. The goal was to connect all 10 provinces by paved road by 1967, Canada’s centennial year.

By 1955, much of the roadways designated as part of the Trans-Canada was unpaved, and significant sections were not even yet built as a rough roadway. The total cost for completing this was going to be $212 million (in 1955 dollars). 1997 figures provided by transport Canada, and includes only the “national highway system”.

The two sections of greatest difficulty were alongside Lake Superior between Sault Ste Marie and Wawa, which was called “The Big Gap” of 265 km (165 mi), and a 147 km (91 mile) section over the Roger’s Pass between Revelstoke and Golden in BC, which eliminated the Big Bend route, which was going to be flooded by the Mica Dam project flooding vast sections of the Columbia River.

In Ontario, a right of way needed to be cleared through virgin forest for 98 of the 165 miles and 25 bridges needed to be built, but in September 1960 that stretch was officially opened.

The Rogers Pass route followed some of the early tracks of the trans-continental railway that were abandoned years ago as too steep for trains, with the addition of a number of snow sheds to protect the highway from the many winter avalanches (the area gets about 200 ft of snowfall each year) and rockslides This stretch was opened June 30, 1962, and marked the official completion of the Trans-Canada (though at that time about half the 7,770 kilometres was still gravelled).

The Rogers Pass route followed some of the early tracks of the trans-continental railway that were abandoned years ago as too steep for trains, with the addition of a number of snow sheds to protect the highway from the many winter avalanches (the area gets about 200 ft of snowfall each year) and rockslides This stretch was opened June 30, 1962, and marked the official completion of the Trans-Canada (though at that time about half the 7,770 kilometres was still gravelled).

BC continued work to improve the highway through the canyon along the Fraser River by blasting several tunnels, with the final two opening in 1966. By 1963, according to the accounts of traveller Edward McCourt, most of Newfoundland was still in the process of being paved.

Over recent years, much of the focus has been on “twinning” which puts at two lanes in each direction, divided by a median. This is equivalent to the standards for the US Interstate system.

All provinces have twinning programs underway, starting around major population centres.

British Columbia has twinned the Lower Mainland and the Coquihalla, providing fast access between West Vancouver and Kamloops. The sections from Kamloops to the Alberta border are underway, but widening the highway through rugged and mountainous terrain (and where the railroad and the first 2-lanes of highway have claimed the easiest/best terrain) is both challenging and expensive. From Kamloops to the Alberta border they are twinning where possible, but where that cannot be done, BC is building a third passing lane every few kilomtres where terrain permits.

Alberta’s stretch is complete including the the twinning in federally-managed Banff National Park, along with the addition of animal bridges, and the completion of Stoney Trail bypass around Calgary. Saskatchewan and Manitoba are fully twinned with by-passes around Moose Jaw, Regina, Brandon, and Winnipeg. The last part of the highway untwinned is through Whiteschell and Falcon Lakes Provincial Parks, adjoining Ontario.

New Brunswick has been aggressive, twinning a new stretch in 2003, between Moncton and Fredericton, connecting to the long-twinned Saint John River Valley section, taking an hour off the travel time through the province.

Nova Scotia and Newfoundland have already twinned the high traffic sections, including a short toll section in Nova Scotia over the Cobequid Pass.

Ontario has focused on twinning the #69/#400 from Toronto north to Sudbury, and building bypasses around major communities like Kenora, Thunder Bay, Sault Ste Marie, Sudbury, and North Bay. The Ottawa Valley section (now #417) from Carp through Ottawa to the Quebec border has been twinned for many years. Highway 17 is being twinned the 39 l, from Kenora to the Manitoba border over the next decade(2030)

Quebec has twinned AutoRoutes form the Ontario border through/round Montreal and east to Quebec City. They are now working on the section from Quebec City to Riviere du Loup and #185 south to the New Brunswick border at Edmundston.